A Hundred Years of Fire and Earth – San-he Tile Kiln/製瓦百年大家 三和瓦窯

A Hundred Years of Fire and Earth – San-he Tile Kiln

◎English translation: Peng Hsin-yi ◎Photos by Pao Chung-hui

◎English translation: Peng Hsin-yi ◎Photos by Pao Chung-hui

Tile production used to be the most prominent industry in Kaohsiung. Dashu's soil is mostly fine-grain natural clay, the raw material for bricks and tiles. Because deposits are close to the surface and can be exploited easily, the entire district was devoted to the manufacture of bricks and tiles. The industry's heyday was the 1950s when as many as 20 tile workshops and 80 kilns produced bricks and tiles around the clock. However, as cities developed and high-rise buildings became the norm, people stopped constructing houses with tile roofs. The workshops disappeared one by one. Today, only two tile workshops still operate in Taiwan: Liuchia Tile Kiln in Tainan and San-he Tile Kiln in Dashu.

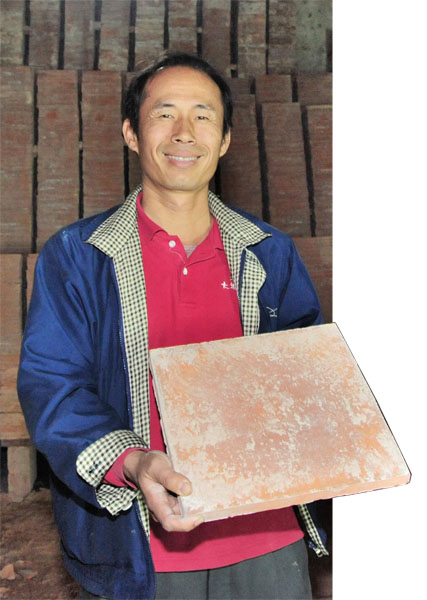

San-he was founded in 1918. The current owner is Mr. Li Chun-hung, the fourth-generation kiln master. Bearing knowledge and experience accumulated through a hundred years of fire and clay, San-he continues to produce red tiles of the type that used to, but no longer, cover the roof of every Taiwanese house. Well lit thanks to skylights, it has two kinds of kiln: a rectangular kiln and two "turtle" kilns. The latter resemble igloos in terms of shape if not color. These kilns are precious antiques in their own right, and there are trade secrets and gems of professional knowledge which took the Li family a century to perfect.

The turtle kilns are almost seven meters high and gigantic inside, whereas the rectangular kiln is much smaller. The turtle kilns are used for tiles, while the rectangular kiln is specifically for baking bricks. The mechanism for baking tiles is similar to that of baking bricks, but the production process for tiles is a bit more complicated and takes longer. When tiles are made, the clay is first shaped in molds. The unfired tiles are then left to dry for about a month before experienced kiln masters pile them up inside of the kiln. This is where knowledge and experience are crucial. Every element can affect the quality of the whole kiln, and is taken into consideration: the size and thickness of each brick or tile, where they are placed, and how much space there should be between each one to ensure even heat distribution. Firing begins with the burning of wood; the temperature is kept relatively low, around 300 degrees Celsius (572°F), for about 30 days. By the end of that stage, the tiles are dried inside and out. Only then does the kiln master switch to burning rice husks. This fuel boosts the kiln's temperature to 1,050 degrees Celsius (1922°F) for another 40 days. The work is not over even after the fire has been extinguished. The bricks and tiles need to stay inside the kiln so they cool slowly. The temperature inside gradually evens out, ensuring each piece is baked to perfection. The firing is grueling work; the kilns are watched every hour of the day, workers being divided into three groups and serving in shifts to monitor and adjust the fire. When break the kiln's seal, the kiln master knocks out only one of the seal's bricks, so the heat inside is gently released. This allows the temperature inside to adjust slowly before the whole seal is broken and removed. Mr. Li says he can knock a piece of tile with his knuckle, and from the sound it makes – as well as its color and luster – tell if the firing has been successful. Today, San-he is a trusted supplier of red bricks and tiles for customers restoring or maintaining heritage sites or buildings which are national treasures.

The turtle kilns are almost seven meters high and gigantic inside, whereas the rectangular kiln is much smaller. The turtle kilns are used for tiles, while the rectangular kiln is specifically for baking bricks. The mechanism for baking tiles is similar to that of baking bricks, but the production process for tiles is a bit more complicated and takes longer. When tiles are made, the clay is first shaped in molds. The unfired tiles are then left to dry for about a month before experienced kiln masters pile them up inside of the kiln. This is where knowledge and experience are crucial. Every element can affect the quality of the whole kiln, and is taken into consideration: the size and thickness of each brick or tile, where they are placed, and how much space there should be between each one to ensure even heat distribution. Firing begins with the burning of wood; the temperature is kept relatively low, around 300 degrees Celsius (572°F), for about 30 days. By the end of that stage, the tiles are dried inside and out. Only then does the kiln master switch to burning rice husks. This fuel boosts the kiln's temperature to 1,050 degrees Celsius (1922°F) for another 40 days. The work is not over even after the fire has been extinguished. The bricks and tiles need to stay inside the kiln so they cool slowly. The temperature inside gradually evens out, ensuring each piece is baked to perfection. The firing is grueling work; the kilns are watched every hour of the day, workers being divided into three groups and serving in shifts to monitor and adjust the fire. When break the kiln's seal, the kiln master knocks out only one of the seal's bricks, so the heat inside is gently released. This allows the temperature inside to adjust slowly before the whole seal is broken and removed. Mr. Li says he can knock a piece of tile with his knuckle, and from the sound it makes – as well as its color and luster – tell if the firing has been successful. Today, San-he is a trusted supplier of red bricks and tiles for customers restoring or maintaining heritage sites or buildings which are national treasures.

Mr. Li sees San-he as more than just trying to keep a family business running. He has become very aware of his role as the living heir of a faded tradition, and in recent years he has began to experiment by  offering guided tours, tile-making experience courses, and using clay to make other arts-and-crafts products so this ancient material can grow new roots into the lives of modern Taiwanese people.

offering guided tours, tile-making experience courses, and using clay to make other arts-and-crafts products so this ancient material can grow new roots into the lives of modern Taiwanese people.

製瓦百年大家 三和瓦窯

◎文/侯雅婷 ◎攝影/鮑忠暉

瓦窯業曾為大樹區具代表產業之一,當地土質細密,在地面上即可取得煉磚瓦所須的自然黏土,於是形成瓦窯聚落,50年代發展至最顛峰,最高紀錄有20幾家瓦窯場、80幾座瓦窯。隨著社會變遷與建築型態改變,磚瓦需求遽減,全台仍在生產中的瓦窯廠僅剩高雄的「三和瓦窯」和另一家台南的瓦窯廠。

三和瓦窯自1918年開始製瓦,迄今傳承至第四代李俊宏,以百年製瓦功力,繼續生產著記憶中代表台灣的朱紅色磚瓦。走進三和瓦窯的瓦寮,光線從紅瓦屋頂的撒了下來,瓦寮一隅矗立著1座四角窯和2座龜仔窯,古蹟級的瓦窯透著學問。

相較於龜仔窯,四角窯容納空間小許多,專門用以燒磚,燒製期程約耗時1個月;而龜仔窯容納空間高度約為7米;四角窯和龜仔窯煉瓦過程大致相同,只是龜仔窯疊窯時複雜度更高,煉製期程更長。龜仔窯煉瓦時,須先待堆疊的土坯陰乾,耗時約1個月,之後疊窯費時1星期,疊窯的每一個步驟更是經過專業判斷後的縝密安排,老師傅須就不同類型和厚度的磚、擺放位置、預留火路(磚與磚間的空隙)以及火喉掌控,全憑經驗,這些都攸關一爐磚瓦煉製的成敗。之後再以木材連續窯燒30天,以300度低溫烘乾土坏,再以稻殼燒40天,溫度提昇至1050度後,土坏焠煉成磚,再以磚塊封窯2星期,使諾大的窯洞,從上到下堆疊的磚瓦均能透過慢熱的作用熟透。煉瓦時火不能斷,一天三班,每班三個工作人員,確保窯火運作順暢。拆窯時,會先敲開第一塊磚,讓熱氣慢慢釋出,再將封住的牆面拆掉。李俊宏談起,他會用手背輕敲瓦片,聽聲音和看色澤來判斷煉瓦是否成功。這個極度仰賴人力的工作,每個步驟全憑累積的經驗和智慧,煉製出朱紅色的磚瓦,成了古蹟、古厝修復的建材來源。

相較於龜仔窯,四角窯容納空間小許多,專門用以燒磚,燒製期程約耗時1個月;而龜仔窯容納空間高度約為7米;四角窯和龜仔窯煉瓦過程大致相同,只是龜仔窯疊窯時複雜度更高,煉製期程更長。龜仔窯煉瓦時,須先待堆疊的土坯陰乾,耗時約1個月,之後疊窯費時1星期,疊窯的每一個步驟更是經過專業判斷後的縝密安排,老師傅須就不同類型和厚度的磚、擺放位置、預留火路(磚與磚間的空隙)以及火喉掌控,全憑經驗,這些都攸關一爐磚瓦煉製的成敗。之後再以木材連續窯燒30天,以300度低溫烘乾土坏,再以稻殼燒40天,溫度提昇至1050度後,土坏焠煉成磚,再以磚塊封窯2星期,使諾大的窯洞,從上到下堆疊的磚瓦均能透過慢熱的作用熟透。煉瓦時火不能斷,一天三班,每班三個工作人員,確保窯火運作順暢。拆窯時,會先敲開第一塊磚,讓熱氣慢慢釋出,再將封住的牆面拆掉。李俊宏談起,他會用手背輕敲瓦片,聽聲音和看色澤來判斷煉瓦是否成功。這個極度仰賴人力的工作,每個步驟全憑累積的經驗和智慧,煉製出朱紅色的磚瓦,成了古蹟、古厝修復的建材來源。

肩負著百年家業,李俊宏基於一份使命感,繼續窯場運作,他意識到,此舉記錄下凋零的瓦窯業,同時透過瓦窯文化導覽、動手做瓦等課程,以及開發磚雕工藝品等方式,將磚雕工藝應用於生活,開創出百年瓦窯廠的另一種可能,讓在地的瓦窯業在這片土地繼續下去,就像是不曾間斷的窯火一般。